Drafty homes drive up energy bills. Maine volunteers are using a simple technique to insulate some of them

Inside an old church basement in Norway, Sharon Harrison stretches a wide, thin sheet of polymer over a rectangular wooden frame. She’s one of a few dozen volunteers inside the church — building the frames and covering them in shrink wrap and foam.

The end result: window inserts that will eventually fit snugly into the drafty windows in her house in Waterford, built back in 1798. She already added some inserts a few years ago.

“And I do not want to replace the windows. I love the old, gravy glass,” Harrison said. “So this was a good alternative to keeping our house from being drafty. It really has made a difference.”

A big difference. It’s warmer inside, and Harrison said her fuel bill has fallen by a third.

“The first year we moved in the house, without these, we were just going through so much fuel. It was ridiculous,” Harrison said. “And there’s been a couple occasions when I’ve taken one out of a window, and you cannot believe the cold difference behind that. It really stopped the drafts.”

Harrison is building these inserts through a program called WindowDressers, through which residents from communities across Northern New England come together in churches and town halls to tape and wrap the frames together. The Norway event was organized by a local group, the Center for an Ecology-Based Economy. By using volunteers, prices stay relatively cheap — around $40 per insert. And they’re free for low-income households.

But while advocates tout this low-cost solution as a way to both reduce bills and cut carbon as part of the state’s plans to move away from fossil fuels, they say tackling Maine’s old, drafty housing stock will require a lot more investment in the years ahead.

“We’ve seen that about 96% of units in Maine, were built before the state even adopted a statewide building energy code, in 2008,” said Jeff Marks, a senior policy advocate and Maine Director for the Acadia Center, a climate advocacy organization.

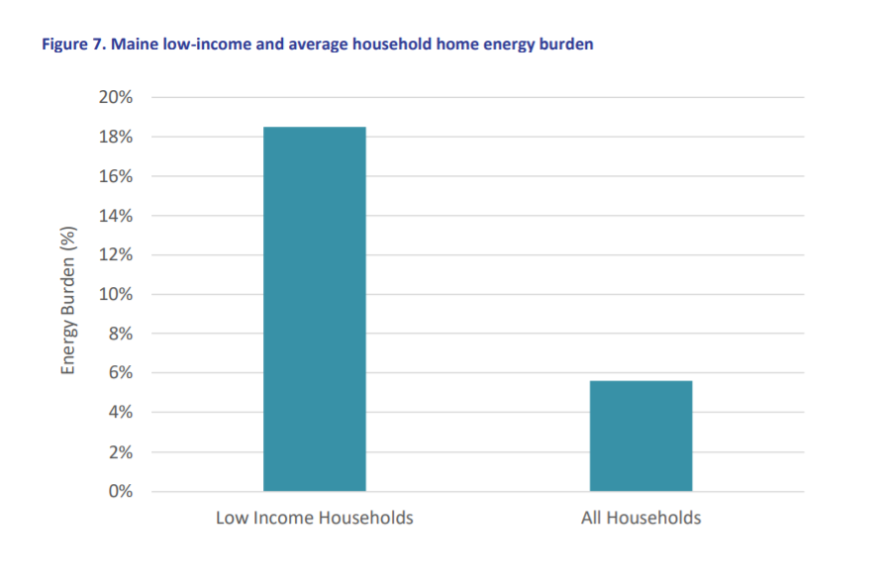

Marks said that while weatherizing those hundreds of thousands of older homes is a huge challenge, it can make a substantial difference — particularly for low-income residents, who spend nearly a fifth of their income on energy alone.

A 2019 report from the Maine Office of the Public Advocate shows the average home energy burden for low income households compared to all households in the state.

“And really, the electrification of homes, with energy efficient heat pumps, are really the next steps. And are the types of investments that Maine really needs to increase over the coming years,” he said.

Some view Maine as a pioneer, as some of the first weatherization programs were created here in the 1970s.

In the decades since, MaineHousing has used funding from the federal Weatherization Assistance Program to seal cracks, close drafts and insulate hundreds of homes a year for low-income residents eligible for heating assistance. More recently, Efficiency Maine has also offered weatherization rebates: up to $3,500 for any resident, and up to $9,600 for those with low-to-moderate incomes.

“That’s anywhere from a third, to maybe as much as 90% of a typical project cost,” said Efficiency Maine Executive Director Michael Stoddard. “It makes a huge difference. And I think that’s a big — that financial incentive really helps people take that action.”

Altogether, the two agencies’ efforts combined weatherized about 2,000 Maine homes this year.

But in order for the state to reach its climate goal of weatherizing 35,000 homes by 2030, that rate will need to nearly double.

State officials say two recent investments have them feeling optimistic they can get there. Earlier this year, the Mills Administration allocated $25 million in federal stimulus money to Efficiency Maine, which the agency estimates will weatherize about 3,500 homes.

And the bipartisan infrastructure bill passed last month contained $3.5 billion for home weatherization nationally — about ten times the program’s annual funding level.

“But we have to remember, these are one-time influxes of cash into the state,” said the Acadia Center’s Jeff Marks. He notes that while the increased attention and funding on weatherization are good steps from state officials, he’d like to see more sustainable funding sources over the long term, such as a fee on heating fuels.

“So the money coming in from the federal government, as well as state money, and Efficiency Maine programs, are good. They’re solid,” Marks said. “But it’s not nearly enough to do everything that we need to do to reach our energy goals.”

And some advocates said that even with funding, doubling the rate of weatherization will also require bolstering the state’s workforce in a tight labor market, which could be a challenge, even with new job training programs.

Back in the church basement in Norway, Jim Gibson of Fryeburg sticks long strips of foam on to the sides of a wooden window insert — it’s one small step that Gibson says he can take to reduce carbon emissions.

“And it doesn’t seem that our politicians are moving too fast in that realm,” Gibson said. “So as I say, I feel as though, one window at a time, I’m trying to make a difference.”

Read the full article at Maine Public here.

Follow us