The Massachusetts Commission on Clean Heat: A Priceless Opportunity

On Monday, Massachusetts’ Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs (EEA) announced that it had convened a new Commission on Clean Heat, the first body of its kind in the nation. According to Governor Charlie Baker’s office, this committee of stakeholders will work to “establish a framework for a long-term decline in emissions from heating fuels.” Acadia Center applauds the Commonwealth for undertaking this important work and underscores the need for this Commission to take its role seriously—Massachusetts cannot meet its climate commitments without eliminating emissions from buildings.

Buildings account for one third of Massachusetts’ greenhouse gas emissions. Federal data[1] and Acadia Center analysis show that space heating and water heating currently account for 70% of residential emissions and about half of commercial building emissions. Tackling these sources of emissions is absolutely crucial to achieving the Commonwealth’s net zero target for 2050.

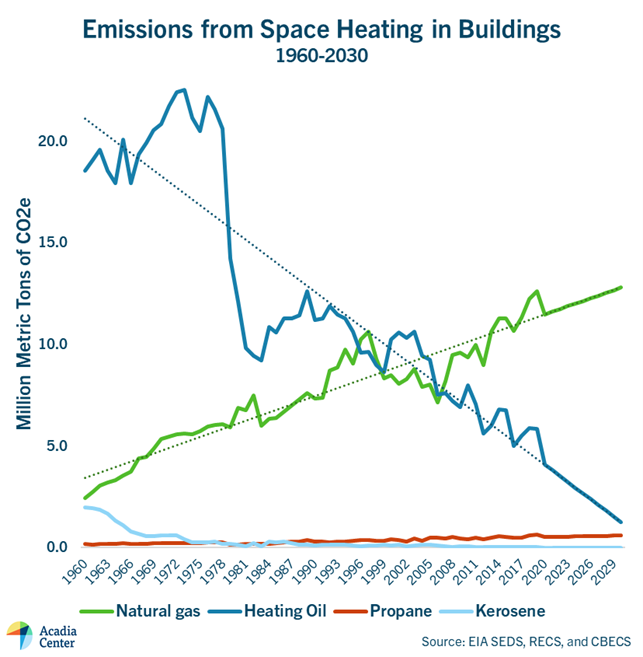

This chart demonstrates that emissions from burning natural gas for space heating in buildings surpassed emissions from burning oil for heating around 2002. Massachusetts is on track for 88% of its heating emissions to come from burning natural gas by 2030.

However, many of the policy details are still to be determined. For a complex, multi-sector topic like heating, the devil is in the details.

Our Over-reliance On Gas

Economy-wide emissions have declined by about 23% in Massachusetts since 1990. Yet emissions from buildings have remained mostly flat. A closer look at the data tells us why: while the use of oil has declined markedly, it has been replaced by another fossil fuel: natural gas. In addition to those that have converted from oil to gas, more than 90% of new housing units in the Northeast are built with gas-fired equipment.[2] As a result, the Commonwealth is on track for natural gas to represent more than 70%—and potentially up to 90%—of its space heating emissions by 2030.

Natural gas is a fossil fuel that emits carbon dioxide when burned. It also consists mostly of methane, itself a greenhouse gas that is 86 times as potent as CO2.[3] It will be impossible for the Commonwealth to continue its reliance on natural gas and still meet its climate targets.

Designing The Cap

Because natural gas already figures so prominently in meeting the heating needs of homes and businesses in Massachusetts, the Commonwealth’s proposed heating fuel emissions cap[4] must be designed in a way that does not encourage more oil-to-gas fuel switching. Converting homes from oil to gas achieves a tiny short-term emissions reduction, but locks in decades of unnecessary emissions in the long run. It also locks consumers into using a fuel that faces volatile price fluctuations[5] and can be damaging to their health.[6]

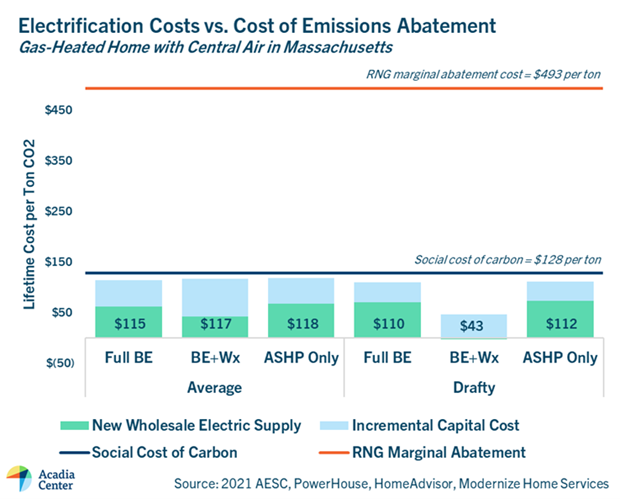

The cost of electrification—i.e. the cost difference between electrification and business-as-usual fossil fuel equipment, plus the cost of new electricity supply—is lower than the cost of emissions to society, and significantly lower than the cost of abating the same amount of CO2 using biogas (RNG).

BE = beneficial electrification

Wx = weatherization

ASHP = air-source heat pump

Average = a home with average building shell efficiency

Drafty = a home with poor building shell efficiency

Using clean, efficient heat pumps to satisfy the Commonwealth’s heating needs is, as the 2050 Roadmap acknowledges, the most cost-effective and the easiest-to-deploy strategy for decarbonizing buildings.[7] In fact, Acadia Center analysis shows that gas-to-heat-pump conversions are cheaper for society than doing nothing: per ton of carbon abated, the cost of whole-home electrification in a gas-heated home is less than the cost of future property and infrastructure damage due to the impacts of climate change—a metric known as the “social cost of carbon.”

Electrification Is The Answer

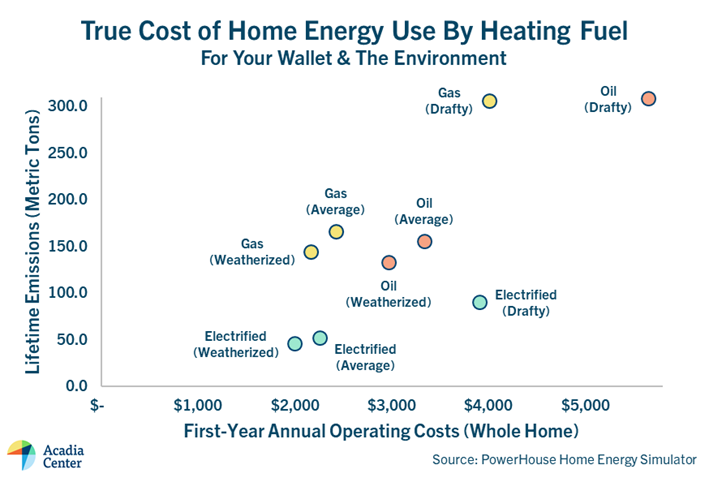

Energy bill and emissions impacts can vary widely between buildings, depending on their location and their building shell efficiency. Regardless of these variations, whole-building electrification reduces emissions substantially and, in many cases, reduces annual energy costs as well. Combining properly-installed heat pumps with common-sense weatherization measures like insulation and air sealing can reduce bills even further while improving comfort and health.

The Mass Save 2022-2024 Three-Year Plan is set to “fundamentally transform”[8] programs to accommodate more building electrification, better equity outcomes, and more investment in workforce development. As a result, robust financial assistance will hopefully be available to any home or business owner who chooses to convert to heat pumps.

Conclusion

The Commission on Clean Heat is the Commonwealth’s best chance to meaningfully address its worsening overreliance on natural gas. It is essential that the Commission seize this priceless opportunity. State agencies, Massachusetts residents, contractors, and industry actors must come together around policies that dramatically reduce emissions from buildings while improving equity and health outcomes. Acadia Center is looking forward to working with Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs and the members of the Commission to promote policies and programs that achieve these goals.

Footnotes

[1] U.S. Energy Information Administration. Residential Energy Consumption Survey (RECS) and Commercial Buildings Energy Consumption Survey (CBECS). RECS: https://www.eia.gov/consumption/residential/ ; CBECS: https://www.eia.gov/consumption/commercial/

[2] HUD Survey of Construction (SOC): Annual Characteristics of New Housing. The median percentage of all housing units built in the Northeast between 2015 and 2020 that heat with gas is 92%. Data files are available at https://www.census.gov/construction/chars/

[3] IPCC Fifth Assessment Report (AR5), 2014. Summary: https://www.ghgprotocol.org/sites/default/files/ghgp/Global-Warming-Potential-Values%20%28Feb%2016%202016%29_1.pdf

[4] Massachusetts Interim Clean Energy and Climate Plan for 2030. December 30, 2020. Page 29. https://www.mass.gov/doc/interim-clean-energy-and-climate-plan-for-2030-december-30-2020/download

[5] Knoema Commodities Data Hub. See: Natural Gas Henry Hub Spot Price, Annual & Monthly; U.S. Natural Gas Futures Closing Price, Daily; EIA Long-Term Natural Gas Price Projection, Henry Hub. https://knoema.com/infographics/ncszerf/natural-gas-price-forecast-2021-2022-and-long-term-to-2050

[6] Jonathan J. Buonocore et al. “A decade of the U.S. energy mix transitioning away from coal: historical reconstruction of the reductions in the public health burden of energy.” Environmental Research Letters: Volume 16, Number 5. May 2021. https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/abe74c

[7] Massachusetts 2050 Decarbonization Roadmap. December 2020. Page 22. https://www.mass.gov/doc/ma-2050-decarbonization-roadmap/download

[8] Mass Save Program Administrators. “PA Update on 2022-2024 Three Year Plan.” Presented to the Massachusetts Energy Efficiency Advisory Council on September 22, 2021. https://ma-eeac.org/wp-content/uploads/9.22.21-EEAC-3YP-Presenation_FINAL.pdf

Follow us